Some notable musicians are self-taught, but many have a mentor who was an important inspiration. Jovino Santos Neto is a Brazilian artist who was fortunate to have had the singular Hermeto Pascoal as his guide. Pascoal is one of the most important figures in Brazilian jazz and instrumental music. He is known for his great improvisational abilities; his complex, wholly original compositions mixing jazz with northeastern Brazilian idioms; and his ability to create music with whatever instruments or household objects are at hand. Jovino earned his musical credentials playing with Pascoal’s band, “O Grupo,” from 1977 to 1992. Santos Neto functioned as a pianist, flutist, composer, producer, and arranger for O Grupo. Looking back, Jovino recalled how Hermeto expanded his sonic universe. “Hermeto was my school for fifteen years, and I continue to learn from him by studying, practicing and analyzing his music.”

Santos Neto developed into an accomplished composer and musician in his own right and has fused jazz, Brazilian music, and classical music on albums such as Canto do Rio (2003) and Roda Carioca (2006), which garnered Latin Grammy nominations in the category of best Latin Jazz Album, and Live at Caramoor with Weber Iago (2009), which earned a Latin Grammy nomination for Best Instrumental Album. And, just as Pascoal once tutored him, Santos Neto has been a mentor to young musicians for many years in North America; he teaches piano, composition, and jazz ensemble at the Cornish College of the Arts in Seattle.

Jovino was born in Rio in 1954 and grew up in Realengo, a neighborhood in Rio’s western outskirts. At the age of twenty, he left Realengo to study biology at McGill University in Canada. He returned three years later and started playing with Pascoal. Santos Neto embarked on a solo career in 1992, and relocated to Seattle, Washington with his family in 1993. After his move to North America, he was a member of Airto Moreira and Flora Purim’s group Fourth World from 1994 to ’97. He contributed to Purim’s Speed of Light, and was part of Mike Marshall’s Brasil Duets, Ben Thomas’ The Madman’s Difference, and Jesse Stern’s Blues for the Bear, among other recordings. Jovino released his first solo album, Caboclo, in 1997. He has performed as a piano soloist and with symphony orchestras and chamber music groups. The NDR Big Band, Seattle Symphony Orchestra, St. Helens String Quartet, and Trio Vento have performed his compositions.

Jovino still works with Hermeto Pascoal, coordinating international performances of Pascoal’s big-band music. He is a caretaker for Pascoal’s vast body of work, most of which is still unrecorded. Jovino has collected all of Pascoal’s original manuscripts, annotating or transcribing more than a thousand compositions. He edited Tudo É Som (All is Sound), a collection of Pascoal compositions published by Universal Edition. Jovino and Mike Marshall released the album Serenata: The Music of Hermeto Pascoal in 2003.

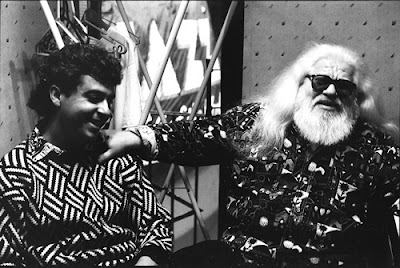

Jovino and Hermeto at the Blue Note in 1991 (photo by Tim Geaney)

Jovino and Hermeto at the Blue Note in 1991 (photo by Tim Geaney)I interviewed Jovino in 2007. This interview is included in a book of my collected Brazilian music interviews that will be published later this year (check this blog for details).

Chris: How did you get involved with the Cornish College of the Arts?

Jovino: I came to Cornish as a student in 1993, and after two semesters I started teaching there, first as a sub, then as an adjunct and now as a full time professor of music there. It's a great place to connect with younger musicians and to keep the creative juices flowing.

Chris: You have been nominated for Latin Grammy awards in the Best Latin Jazz Album category, for Canto do Rio and Roda Carioca. I have been listening a lot to Canto do Rio lately, and I have to confess I find it very difficult to categorize it. I'm hearing jazz of course, along with choro, baião and other northeastern Brazilian rhythms, and classical-music elements.

Jovino: If you find it hard to fit the music into one category, then I have reached my goal of creating universal music based on my personal musical history. As I experience more colors and flavors from the music of the world, my personal style absorbs them and the result will hopefully still bear my musical DNA.

Chris: Could you talk about the musical ingredients that went into Canto do Rio, and perhaps give examples of different fusions of genres, rhythms, harmonies, and instruments in a couple of your songs?

Jovino: If you listen to the opening track, "Guanabara," it starts with a choro groove with pandeiro and clarinet, but the main theme has the hits and the melody of a maracatu for a bit, then it becomes a samba, and the improvisation section in 7/4 meter is something else. I personally don't keep track of these transitions. The process is more organic and fluid during the composition and arranging stages of the creation. "Pedra Branca" is another maracatu with two simple parts that get different harmonies and textures as the tune develops. "Primavera em Flor" is a baião for most of the time, but at one point there is an abrupt change into a xote, where the solos happen. "Sempre Sim" is a simple theme in 7/4 built over a pedal vamp, and the band just played it in a loose way, where everyone improvises at once.

Chris: You have been nominated for Latin Grammy awards in the Best Latin Jazz Album category, for Canto do Rio and Roda Carioca. I have been listening a lot to Canto do Rio lately, and I have to confess I find it very difficult to categorize it. I'm hearing jazz of course, along with choro, baião and other northeastern Brazilian rhythms, and classical-music elements.

Jovino: If you find it hard to fit the music into one category, then I have reached my goal of creating universal music based on my personal musical history. As I experience more colors and flavors from the music of the world, my personal style absorbs them and the result will hopefully still bear my musical DNA.

Chris: Could you talk about the musical ingredients that went into Canto do Rio, and perhaps give examples of different fusions of genres, rhythms, harmonies, and instruments in a couple of your songs?

Jovino: If you listen to the opening track, "Guanabara," it starts with a choro groove with pandeiro and clarinet, but the main theme has the hits and the melody of a maracatu for a bit, then it becomes a samba, and the improvisation section in 7/4 meter is something else. I personally don't keep track of these transitions. The process is more organic and fluid during the composition and arranging stages of the creation. "Pedra Branca" is another maracatu with two simple parts that get different harmonies and textures as the tune develops. "Primavera em Flor" is a baião for most of the time, but at one point there is an abrupt change into a xote, where the solos happen. "Sempre Sim" is a simple theme in 7/4 built over a pedal vamp, and the band just played it in a loose way, where everyone improvises at once.

Chris: Can you tell us about the album that followed it, Roda Carioca?

Jovino: With Roda Carioca the composition process was similar, but with different musicians. This is my first CD recorded in Brazil, and I had the good fortune to have players like Marcio Bahia, Rogério Botter Maio, Hamilton de Holanda, Gabriel Grossi, Marcos Amorim, Fabio Pascoal as well as Joyce and Hermeto Pascoal as guests on the recording.

Jovino: With Roda Carioca the composition process was similar, but with different musicians. This is my first CD recorded in Brazil, and I had the good fortune to have players like Marcio Bahia, Rogério Botter Maio, Hamilton de Holanda, Gabriel Grossi, Marcos Amorim, Fabio Pascoal as well as Joyce and Hermeto Pascoal as guests on the recording.

Jovino at Instrumental SESC Brasil, performing Passareio / Amoreira

Chris:You have collaborated with Airto and Fourth World. What kind of music do they play, and what was the experience like?

Jovino: I learned a lot during my time with Airto, Flora and Fourth World. In that band I was mostly playing keyboards, and I developed a sense of textures and possibilities for using electronic instruments. Airto is a fantastic musician, and I always liked his playing, since I heard him playing the donkey jawbone in "Disparada" way back in the '60s [with Quarteto Novo, backing Geraldo Vandré]. He is a fantastic drummer and percussionist.

Jovino: I learned a lot during my time with Airto, Flora and Fourth World. In that band I was mostly playing keyboards, and I developed a sense of textures and possibilities for using electronic instruments. Airto is a fantastic musician, and I always liked his playing, since I heard him playing the donkey jawbone in "Disparada" way back in the '60s [with Quarteto Novo, backing Geraldo Vandré]. He is a fantastic drummer and percussionist.

Chris:Are you still archiving Hermeto’s compositions? I understand you've filed over 1,000 of his compositions.

Jovino: I am always working on preparing Hermeto's music as a legacy to the musicians of this and the next generations. I have edited one book, Tudo É Som, which was published by Universal Edition, and that book has been important in helping musicians connect with Hermeto's work. This work of preparing and notating Hermeto's music will probably take many more years, since there is so much material, but I do it one day at a time. Eventually more music will be made available using more modern means, like the Internet.

Jovino: I am always working on preparing Hermeto's music as a legacy to the musicians of this and the next generations. I have edited one book, Tudo É Som, which was published by Universal Edition, and that book has been important in helping musicians connect with Hermeto's work. This work of preparing and notating Hermeto's music will probably take many more years, since there is so much material, but I do it one day at a time. Eventually more music will be made available using more modern means, like the Internet.

Chris:Is your archival work for Hermeto helping musicians to perform and record his compositions?

Jovino: This is what I hope. I have received some great feedback and comments from musicians from all over the world. Of course, Hermeto is a legendary musician, but it is very hard to transcribe his music from recordings. It is also very difficult to tell what is written from what is improvised in his work, so I hope to help other musicians access his work.

Jovino: This is what I hope. I have received some great feedback and comments from musicians from all over the world. Of course, Hermeto is a legendary musician, but it is very hard to transcribe his music from recordings. It is also very difficult to tell what is written from what is improvised in his work, so I hope to help other musicians access his work.

Chris: What is the Hermeto Pascoal Big Band exactly?

Jovino: Hermeto has been writing big band charts since the early 1970s. In 1986, 1989 and 1992 he was commissioned by the Danish Radio Big Band to write some more music, which they performed. In 2000 and 2004 another big band was formed with top players in London to perform his compositions, under my direction and with Hermeto as a soloist. We also played in 2005 in France with the Big Band from the Toulouse Conservatory. Hermeto's jazz orchestra charts are challenging and beautiful, audiences really enjoy them. I directed a U.S. premiere of several of them with the Bobby Sanabria Big Band in New York's Merkin Hall in September 2006. [Author's note: Jovino later added that some Hermeto jazz orchestra pieces debuted prior to that in an October 26, 2004 concert with the University of North Texas Jazz Repertory Ensemble, directed by John Murphy at UNT, with Jovino as a guest pianist.].

Chris: What has been the importance of Hermeto as a mentor for you? How did he help you develop as a musician?

Jovino: Hermeto was my school for 15 years, and I continue to learn from him by studying, practicing and analyzing his music. His importance as a mentor to several generations of Brazilian musicians is undeniable. As a teacher, he never "taught", but instead he knew exactly what kind of challenge to place in front of a musician. He knew what kind of language to employ with each one, and how to make musicians with widely different levels of expertise play together harmoniously.

Chris: What were the rehearsals like for O Grupo?

Jovino: Every day was different. We often would spend entire days working on one challenging passage, learning it individually and collectively. He often composed the music in front of us, so we also got to know how to compose, arrange, score and lead a group. At other times he would dismantle the rehearsal by starting some wacky improvised piece of music, and this could lead to new written music. There was never a dull day in the Grupo.

Chris: What were the live performances like for O Grupo?

Jovino: Our sets were never pre-determined, we would often change a piece in the middle into another one. Often there would be guest musicians sitting in with us, or new compositions would be premiered right there in front of the audience. We have played concerts as long as five hours, so this was certainly a stamina-building exercise...

Chris: Can you talk about Hermeto’s harmonic concepts? And how have they influenced you?

Jovino: His harmonic concepts are indeed a new way to look at music. The idea of one tonal center or key signature that we have been using in music for centuries has been replaced with a much deeper and multi-layered approach. His music can be folkloric, regional, popular, jazzy, atonal, but the concept remains as a guiding force. It's hard to explain without an instrument, but its basis is the juxtaposition of simple triads and the avoidance of linear forms such as scales or modes. You can employ it to play all existing music, but it can lead to creation at a much higher level.

Chris: Are there any important trends you see in Brazilian music today, both instrumental and otherwise?

Jovino: I just got back from Brazil, where I travelled through the Nordeste region, from Alagoas to Paraíba and Pernambuco, and I heard a lot of young musicians playing very creative music based on their traditional forms. I heard bands like Sertão Catingoso, O Quadro, Azabumba, and many others who are combining traditional Northeastern forms with contemporary concepts in music. Also in Rio, I heard young choro players like Eduardo Neves, Caio Marcio and Rogério Caetano injecting new life into a 150-year old style. It's certainly encouraging to hear this music and know that in spite of little attention given in the mainstream media, music in Brazil is alive and well.

Chris: Could you comment about the music of your fellow Grupo alumnus, Carlos Malta?

Jovino: Carlos Malta has always been a virtuoso flutist and saxophonist. Recently I saw him on TV playing with carpideiras, women who sing at funerals, and also with some traditional musicians from Goiás. I admire his talent and his creativity.

Chris: Are there any promising young musicians in Brazil that have caught your ear? Perhaps Yamandú Costa, Hamilton de Holanda? Anybody you'd like to talk about?

Jovino: Yes, both Hamilton and harmonica player Gabriel Grossi recorded with me in Roda Carioca. There are far too many young talented musicians to mention. Itiberê Zwarg, with his Orquestra Família, and the Pró-Arte, with their Flautistas Group, have done a lot to bring new players into the scene. Yamandú is an amazing guitarist, as are Marcus Tardelli, Daniel Santiago, Caio Márcio, and Rogério Caetano. There is a great new generation, and I am very pleased to hear them.

Chris: What are your current creative projects?

Jovino: I am always working on a few things at the same time. Right now, I am diving deeply into the music of the Nordeste for my upcoming CD, which will be recorded in August. I am working to bring the beautiful musical languages of the aboio, pífanos, maracatu, frevo and xote into a personal blend that will sound harmonically modern, but without losing its connection to the land. It will be called Alma do Nordeste and will be the result of a research trip I just took through the region, courtesy of a grant from Petrobrás. I am also recording a solo piano CD this week for Adventure Music, and I am writing a piece for twenty percussionists that will be premiered here in Seattle in July.

Chris: Brazilians are known for being eclectic musicians and you are one of the most diverse, ranging across Brazilian and American styles, jazz and classical music, and the avant-garde.

Jovino: I feel happy to be able to connect musically with the entire planet.

Since our interview took place, Jovino has released the albums Alma do Nordeste (2008) and Veja o Som (2010). The latter is a double CD of duets with musicians such as Bill Frisell, Paquito d'Rivera, João Donato, Airto Moreira, Joyce, Paula Morelenbaum, Monica Salmaso, Ricardo Silveira, and Gabriel Grossi.

______________________________________________

Jovino's Favorite Hermeto Pascoal Compositions

In 2010, I asked Jovino to send me a top ten of his favorite recorded Hermeto Pascoal compositions, with a sentence or two about each one. Here is his list:

ONE: "São Jorge" -- one of several horse songs Hermeto has composed, this one was also the very first track I recorded as a member of his group in 1978.

TWO: "Nem Um Talvez" -- also recorded by Miles Davis, this has to be one of the prettiest melodies ever written. Gorgeous tune...

THREE: "Dança da Selva na Cidade Grande" -- this one shows Hermeto’s mastery of wooden flutes and natural sounds and his collage of voices and percussion (including sand, corn, beans, chains and water in the studio). One of several ?Indian? songs by HP.

FOUR: "Missa dos Escravos (Slaves Mass)" -- a very mysterious piece, made famous by the use of pigs in the recording. There’s much more than that, though. The harmony (unusual tuning of the guitar), the flutes and the chants make this tune one of my favorites.

FIVE: "Montreux" -- I watched that one being written in a hotel room in Montreux, Switzerland, in 1979 on the back of a laundry list, just a few hours before we played it in front of a huge crowd. My wife Luzia is Swiss; we were there that day and still remember it fondly...

SIX: "Quebrando Tudo" -- this entirely improvised piece one shows Hermeto’s amazing performance on the clavinet. He created the whole thing on the spot.

SEVEN: "Intocável" -- a beautiful choro, modern and traditional at the same time. The great Raphael Rabello recorded it with us. I always remember his laughter when I hear that tune.

EIGHT: "Três Coisas" -- one of the many examples of the Sound of the Aura, a technique created by Hermeto to harmonize the sound of the human voice. I played all the sounds on this one, built around the voice of the great poet and actor Mario Lago.

NINE: "Série de Arco" -- Hermeto composed this one to accompany my sister Maria Luiza’s routine as a rhythmic gymnast in 1980, first as a solo piano piece, then he arranged it for the Grupo. Wonderful harmonic language, a technical challenge to play. The composition followed her movements as she rolled on the floor and jumped around.

TEN: "Suite Norte, Sul, Leste, Oeste" -- a wonderful collection of short vignettes inspired by the diversity of Brazilian music.

____________________________________________

Select Jovino Santos Neto Discography

(U.S. releases unless otherwise noted)

(U.S. releases unless otherwise noted)

Jovino Santos Neto (solo or with his Quintet)

Caboclo. Liquid City Records, 1997.

Ao Vivo em Olympia: Live in Olympia. Liquid City Records, 2000.

Canto do Rio. Liquid City Records, 2003.

Roda Carioca. Adventure Music, 2006.

Alma do Nordeste. Adventure Music, 2008.

Veja o Som See the Sound. Adventure Music, 2010.

Caboclo. Liquid City Records, 1997.

Ao Vivo em Olympia: Live in Olympia. Liquid City Records, 2000.

Canto do Rio. Liquid City Records, 2003.

Roda Carioca. Adventure Music, 2006.

Alma do Nordeste. Adventure Music, 2008.

Veja o Som See the Sound. Adventure Music, 2010.

Jovino Santos Neto & Weber Iago

Live at Caramoor. Adventure Music, 2009.

Live at Caramoor. Adventure Music, 2009.

Richard Boukas & Jovino Santos Neto

Balaio. Malandro Records, 2000.

Balaio. Malandro Records, 2000.

Wolfgang "Humbucker" Frisch, Dr. Nachstrom, et al.

Rhythmic Fission: Digital Revisions of Classic Trax. RCA, 2004. (included Jovino Santos Neto & Tamara L. Weikel’s "Ritual Rhythm," based on Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring).

Rhythmic Fission: Digital Revisions of Classic Trax. RCA, 2004. (included Jovino Santos Neto & Tamara L. Weikel’s "Ritual Rhythm," based on Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring).

Mike Marshall & Jovino Santos Neto

Serenata: The Music of Hermeto Pascoal. Adventure Music, 2003.

Serenata: The Music of Hermeto Pascoal. Adventure Music, 2003.

Hermeto Pascoal (with Jovino Santos Neto in O Grupo)

Zabumbê-Bum-Á. WEA (Brazil), 1979.

Ao Vivo em Montreux. WEA (Brazil), 1980.

Cérebro Magnético. WEA (Brazil), 1980.

Hermeto Pascoal e Grupo. Som da Gente (Brazil), 1982.

Lagoa da Canoa, Município de Arapiraca. Som da Gente (Brazil), 1984.

Brasil Universo. Som da Gente (Brazil), 1985.

Só Não Toca Quem Não Quer. Som da Gente (Brazil), 1987.

Festa Dos Deuses. PolyGram (Brazil), 1992.

Zabumbê-Bum-Á. WEA (Brazil), 1979.

Ao Vivo em Montreux. WEA (Brazil), 1980.

Cérebro Magnético. WEA (Brazil), 1980.

Hermeto Pascoal e Grupo. Som da Gente (Brazil), 1982.

Lagoa da Canoa, Município de Arapiraca. Som da Gente (Brazil), 1984.

Brasil Universo. Som da Gente (Brazil), 1985.

Só Não Toca Quem Não Quer. Som da Gente (Brazil), 1987.

Festa Dos Deuses. PolyGram (Brazil), 1992.

Joyce Yarrow & Jovino Santos Neto.

Total Reflex. Independent, 2000.

Total Reflex. Independent, 2000.

Jovino Santos Neto Bibliography

Tudo é Som (ed.). Vienna: Universal Edition, 2001.World Music Brazil: Play-Along Flute. Universal Edition, 2008.

*Top Photo of Jovino Santos Neto by Lara Hoefs (Courtesy Jovino Santos Neto)