Carnaval in Brazil 2017

Olá Brasil

To find a Brazilian CD or MP3:

Antonio Adolfo: Hybrido

Kudos to Antonio Adolfo, who just received a Grammy nomination for the best Latin Jazz album for Hybrido – From Rio To Wayne Shorter. On it, Adolfo interprets standards by Shorter, including "Speak No Evil" and "E.S.P." Antonio is backed by the likes of Lula Galvão (electric guitar) and Jorge Helder (double bass). Shorter is a legendary composer and saxophonist who played with Art Blakey and Miles Davis before co-founding the fusion group Weather Report. He has also collaborated with Milton Nascimento and other Brazilian musicians for decades. Adolfo is a master of fusing jazz and Brazilian styles, has composed MPB standards such as "Sá Marina" (Pretty World), and has been an important figure in Brazilian music since the 1960s. Here, he adds his usual deft touch to some great material. Highly recommended. The album was also nominated for a "Latin Grammy" award in 2017 in the Best Latin Jazz/Jazz category. Available from: AAM Records, 2017.

Rio Carnaval 2018

February, which featured ample political protest

and were won by Beija-Flor de Nilopolis.

and the Popular Music of Brazil

by Chris McGowan and Ricardo Pessanha (Temple University Press)

Brazilian Harpist Cristina Braga Explores Samba, Jazz and Love

(published November 21, 2013 in The Huffington Post)

The first recordings of samba occurred nearly one hundred years ago and of bossa nova more than fifty years ago. Neither genre has ever been associated with the harp, but lately the venerable stringed instrument has expanded its presence in Brazilian popular music thanks to Cristina Braga, who is the first harpist with the Teatro Municipal symphonic orchestra in Rio de Janeiro and a crossover artist who freely roams between classical music, samba, bossa nova and even rock and roll. Along with recording sixteen albums, the 47-year-old Braga has performed or recorded with Brazilian music luminaries Gal Costa, Marisa Monte, Ana Carolina, Zeca Baleiro and Lenine, with the rock band Titãs, and on the United Kingdom of Ipanema DVD with bossa icon Roberto Menescal and Andy Summers (The Police).

Braga’s new album Samba, Jazz and Love (Enja Records, 2013) features her vibrant, virtuoso harp playing and sultry, breathy vocals in impeccable renderings of samba and bossa classics. The flugelhorn and vibraphone, two other instruments seldom heard in those genres, are also part of the mix, performed by Jessé Sadoc (who also plays trumpet) and Arthur Dutra, respectively. The album was produced by Braga’s husband Ricardo Medeiros, a double bassist whose dynamic bass lines underpin the overall sound. And Joca Moraes adds just the right rhythmic embellishments of alfaiadrums (commonly used in maracatu) and the pandeiro (Brazilian tamborine).

The original concept of the album was very simple. Braga comments, “We wanted to make samba, jazz and love (laughs). We wanted to do something more spontaneous. The instruments were recorded in twelve hours.” Bossa nova, which is an offshoot of samba, supplied part of the repertoire and there are four songs by Antonio Carlos Jobim alone.

The harp creates a different musical universe for the samba and bossa standards on the album, adapting bossa’s familiar plucked guitar chords and expanding the tonal palette and harmonic range. “I think the way the harp is played transforms the music. It becomes different, with the harmonics made by the harp and by the way Cristina plays as a harpist. To not imitate another instrument, but to really be another instrument,” says Medeiros. “For example, the chords of the harp can be really large. With the harp it’s very natural to do a chord with five octaves, something that few instruments can do.”

Medeiros notes that the song has "a very difficult harmony, principally on the harp, where there’s a lot of modulation. And it’s difficult to sing also, but it’s a fascinating song. When we thought about doing this album, we wanted to do something with ‘Desafinado.’ We fell more and more in love with the song, when we transferred the harmony to the harp, when we made the arrangement for the group. All the research was fascinating; it was a great process.The band, all of whom are fine musicians, get to stretch out with more extended soloing in a haunting, compelling instrumental version of the lesser known gem “Triste de Quem,” composed by Moacir Santos and Vinícius de Moraes (bossa nova’s most important lyricist), and recorded in 1963 by Elizeth Cardoso.

The album opens with “Love Parfait,” a new tune composed by Medeiros and lyricist Bernardo Vilhena that evokes a nostalgic Parisian ambiance. "In the beginning, I was trying to do something very simple, a simple melody with a dense harmony. I did the first part twenty years, when I was living in London and my son was born. I had an inspiration and thought that it was a perfect love. I worked with Bernardo on the second part, and his idea of doing a section in French was the key. It became a song that suggests a French café, antiquity."

One of the most compelling songs is Jobim’s lilting “Chovendo na Roseira” (sometimes titled “Children’s Games” in English), an instrumental version highlighted by Sadoc’s honeyed trumpet soloing, Dutra’s hypnotic vibraphone playing and Braga’s lively harp work, which ranges from ethereal to slightly edgy. “The first time I heard Jobim was on an album with “Chovendo na Roseira,” which I thought was really beautiful,” recalls Braga. Samba Jazz & Love also includes Jobim’s “Canta Mais” (Sing More), Candéia’s “Preciso Me Encontrar” (I Need to Find Myself) and the album’s only English tune, “Rio Paraiso” (Paradise River) by Alberto Rosenblit and Paulinho Tapajós.

Braga often surprises the listener with her rhythmic approach on the harp to many songs, as in the overtly jazzy, energetic “Só Danço Samba”; another example (not on this album) is her powerful "A Floresta Amazônica." She observes, “Even today, if people think about a concert with harp, they think it’s going to be a classical thing, a beautiful, very sweet thing. And when we start playing the more rhythmic things, people go, “Huh? You can also do this with the harp?”

“I try to do something different, something harpistic, something Brazilian,” concludes Braga. “The harp is an instrument that has a long history. I think it’s great that it has the form of the map of Brazil.”

For many years, Braga also taught harp at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ) and in 2003 she founded one of the most intriguing musical festivals in the world, the Festival Vale do Cafe. The ten-day event takes place in the historic, verdant “Coffee Valley” located over the mountains and about two hours from Rio. Instrumental music of many types (including classical, choro, regional and jazz) and traditional folkloric music and dance are performed in the valley’s small towns and in grand settings at 19th century coffee plantations.

Luciana Souza: A Bossa Nova Baby Makes Her Mark in the Jazz Realm

(published January 4, 2014 in The Huffington Post)

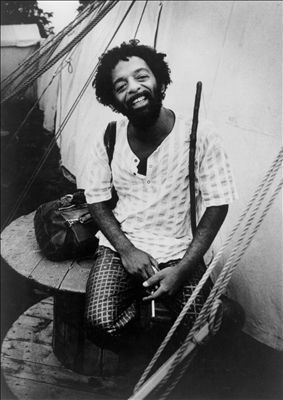

Naná Vasconcelos: Storytelling with Percussion

(published on March 16, 2016 in The Huffington Post)

Vasconcelos was a master of the berimbau, a musical bow from Bahia with a single metal string and a resonating gourd, which he turned into a unique solo voice. His peer Airto Moreira called him “the best berimbau player in the world.”

He was also adept with most other Brazilian percussion instruments, which he combined with layered vocals, handclaps and body percussion. He created irresistible rhythmic waves or engaged in spirited dialogues with other musicians. Sometimes he created dense atmospheres of sound, in which rustles, rattles and rumbles moved with captivating rhythms or clashed in unearthly cacophony.

“He went beyond keeping time and creating just a mood, his thing was deep—he created a sense of place and time in music. When you heard him play, you understood something more about the music. He dove into the story of each song and gave you a reason to stay on. Very few percussionists can do that,” comments Grammy award-winning jazz vocalist Luciana Souza.

Vasconcelos’s collaborations with leading figures from free jazz and fusion put him at the forefront of the world’s percussionists. Naná generated such a distinctive voice with his percussion that he was able to hold his own in duos and trios with musical heavyweights. He teamed with Egberto Gismonti on Dança da Cabeças and Duas Vozes, with Don Cherry and Collin Walcott for three Codona albums, with Pat Metheny and Lyle Mays on As Falls Wichita, So Falls Wichita Falls, with Jan Garbarek and John Abercrombie on Eventyr, and with Milton Nascimento and Herbie Hancock on Miltons.

Juvenal de Holanda Vasconcelos (Naná was his nickname) was born on August 2, 1944 in the coastal city of Recife, which is home to a rich musical heritage that includes genres like maracatu and frevo. As a youth, he learned to play the drums of maracatu as well as most other Brazilian percussion instruments, and became adept with the berimbau, an instrument associated with the martial art capoeira.

In the late ‘60s, he toured with Gilberto Gil and was part of Quarteto Livre with northeastern singer-songwriter Geraldo Azevedo. For a time he was part of the seminal Som Imaginário band, which mixed Brazilian music, jazz and rock and backed Milton Nascimento. His playing caught the attention of saxophonist Gato Barbieri, with whom he started touring. He subsequently spent a few years in Paris and while there worked with disturbed children in a psychiatric hospital, using music as a form of creative therapy. His experiences there would inform his work: Vasconcelos saw how music could transform and improve people’s lives. During this era, he found time to record his first solo album, Africadeus (1973).

In 1979 he formed Codona with trumpeter Don Cherry and percussionist Collin Walcott. The trio released three highly regarded albums for ECM that mixed free jazz and cross-cultural improvisation.

Vasconcelos expanded his audience greatly when he played percussion and sang with the Pat Metheny Group, beginning with Metheny and Mays’ 1981 As Falls Wichita, So Falls Wichita Falls. “He was a total joy to work with,” keyboardist Mays told me in an interview for my book The Brazilian Sound. “One of the things that I most enjoyed about playing with Naná was that he was interested in working with me as a synthesizer player to come up with combination textures that neither of us could do alone. He took things a step further, using his voice together with his instrument and with my instruments. Naná broadened our soundscape, and he added charisma, another focal point of attention on stage.”

On his website, Pat Metheny adds, “In addition to being one of the best percussionists in music, Naná was an amazing, wonderful person. Everywhere he went (berimbau always nestled on his shoulder) he made friends and brought an infectious joy to the people around him. His laugh was contagious and his ability to bring happiness to any situation spilled over to the bandstand.”

Vasconcelos also appeared on Metheny’s Offramp and Travels, before moving on to other projects. Along with releasing his own albums, Vasconcelos enhanced the works of many artists, in and out of Brazil. One noteworthy example is Lenine’s Na Pressão (1999), on which Naná played shakers, a talking drum and other instruments on the album’s dramatic title track. He also recorded with Brazilian musicians Marisa Monte, Caetano Veloso, Alceu Valença, Eliane Elias, Joyce, Toninho Horta, Luiz Bonfá, Badi Assad and Mônica Salmaso, along with those mentioned above and many others.

In addition, Vasconcelos recorded and/or performed with Miles Davis, Art Blakey, Tony Williams, Ralph Towner, Paul Simon, B. B. King, the Talking Heads, Leon Thomas, Jean-Luc Ponty, Jon Hassell, Harry Belafonte, Claus Ogerman, Ginger Baker, Jack DeJohnette, Carly Simon, and the Yellowjackets.

Nana’s many fine solo works, such as Saudades for ECM (1979), Bush Dance (1986), Rain Dance (1989), Storytelling (1995) and Chegada (2005) are like sound encyclopedias, beautiful elaborations of rhythmic and textural possibilities. His album Sinfonia and Batuques won a Latin Grammy award in 2011 for Best Native Brazilian Roots Album.

Vasconcelos returned every year to Recife to take part in Carnaval celebrations and lead a large group of maracatu drummers and singers, one of his many projects that supported Afro-Brazilian culture. When he died, these and other local musicians paid musical tribute to him in a procession through the streets of Recife, on the way to where he was buried.

Brazilian keyboardist, composer and music educator Antonio Adolfo reflects, “He grew tremendously when he traveled and lived outside Brazil. He developed a tremendous technique mixed with all his cultural background—presenting the berimbau to the world along with all his work with percussion in general—and became one of the most important percussionists of all time.”

Gaby Amarantos: The Muse of Tecnobrega Boosts Brazil's Latest Musical Export

(published November 9, 2011 in The Huffington Post)

Singer Gaby Amarantos and DJ João Brasil’s tecnobrega version of Antonio Carlos Jobim’s “Águas de Março” (Waters of March) is either an innovative interpretation for the dance floor or a desecration of one of the greatest songs of the 20th century. Or both. The recording can be heard on YouTube and downloaded from numerous online stores or sites. It is an example of the dance-oriented tecnobrega style, which emerged in the last decade in Belém, the capital of Pará state in the Amazon, and is the latest Brazilian music export to enliven European clubs. It also carries the “mashup” touch of DJ João Brasil, who is from Rio and now resides in London.

Gaby (or “Gabi”) is the current “queen of tecnobrega,” being the style’s most prominent female star, and a new ambassador for her state’s regional music. She has led the band TecnoShow since 2002 and appeared on nationally popular Brazilian television shows like Domingão do Faustão. The full-figured vocalist was born in 1980 and grew up in Jurunas, a poor neighborhood on the outskirts of Bélem. Amarantos wears sexy, outlandish outfits that are surreal in a low-budget Lady Gaga way. Usually, she performs with a supporting cast of similarly clad dancers.

Jobim’s “Águas de Março” was first recorded in 1972 and is a Brazilian and global standard. The late jazz critic Leonard Feather termed it “one of the 10 most beautiful songs of the century.” Jobim and Elis Regina recorded it with an unforgettable duet on Elis & Tom (1974), often cited in polls as the most popular Brazilian album of all time. Gaby’s interpretation of “Águas de Março” is brassy and sometimes strident, and there is none of the sensitivity present in the great performances of the song. Producer DJ João Brasil’s accompaniment is stripped down, with a synthesizer that sounds like a toy keyboard (which it probably was). The samba/bossa beat is gone, replaced by tecnobrega’s simple, snappy rhythm, delivered via drum machine. Jobim’s great harmonies are mostly missing in action. “Águas de Março” is such a national classic that the tecnobrega version is almost as outrageous as when Jimi Hendrix tore up the “Star Spangled Banner” on the electric guitar at Woodstock. Defenders of the song will most likely fit it into Brazil’s Tropicalista tradition of cannibalizing musical standards and styles, and mixing erudite and popular, the high and the low brow.

Tecnobrega is noteworthy for having created a new musical business model, one that has gotten rid entirely of record companies and radio stations. Tecnobrega artists take advantage of cheap available technology, often using personal computers as home studios. Composers freely allow the DJs or producers to copy the music and sell it on CDs that cost as little as $1.50 apiece. The “pirates” become distributors, and the artists gain exposure (but usually zero royalties) through the distribution of their work to the public. The DJs work at huge festas de aparelhagem (sound system parties), which move from location to location, and they can turn unknown songs into instant hits. The shows can include smoke machines, laser displays and giant video screens. There are an estimated 4,000 such events per month, or more, in greater Belém.

Hitherto anonymous artists become well known overnight and can put together bands that may consist of just a keyboardist and vocalist, and go to play at the sound system events and in clubs. Musicians make their money from live performances, not from recordings, except those they sell themselves at shows. Recorded music has become a smaller share of an artist’s income in the rest of the world as well, but in Belém the transition has been greatly accelerated. The new model is so successful in Pará that tecnobrega artists release several hundred albums per year.

Whatever one thinks of tecnobrega, it is part of the ongoing fusion of electronic dance music with Brazilian styles that has also resulted in the creation of funk carioca, Brazilian hip hop, and tecnoforró. Many in Brazil find tecnobrega unmusical and unlistenable, yet many others there and overseas are dancing to it. How would Jobim have reacted to Gaby’s interpretation of “Águas de Março”? I don’t think he would have liked tecnobrega. But I’m pretty sure he would have been amused by Amarantos and pleased with the incredible diffusion of his compositions, so many decades later.

Check out these related YouTube links: Gaby Amarantos and DJ João Brasil, “Águas de Março”, Tom Jobim & Elis Regina (live), “Águas de Março” and Banda Tecno Show with Gaby Amarantos, “Principe Negro.”

My book, The Brazilian Sound: Samba, Bossa Nova and the Popular Music of Brazil, written with Ricardo Pessanha, is available now in print and digital editions. It discusses the music of Belém, lambada, guitarrada and tecnobrega at greater length, along with other Brazilian music genres.

Lenine's Brings His Musical Bridge to Central Park

(published July 18, 2014 in The Huffington Post)

The Maurício de Nassau bridge in Recife is a replica of a bridge in Amsterdam and a reminder of when Holland ruled northeastern Brazil in the early 17th century. It is also the inspiration for “The Bridge” concert series featuring Brazilian singer-songwriter Lenine and Holland’s Martin Fondse Orchestra. After having toured Europe and the Americas, the show will arrive at Central Park’s Summerstage Festival in New York on July 19th.

For Lenine, crossing the bridge is a metaphor for leaving one’s proverbial island, connecting with others, and broadening one’s horizons, which he explored in the song “The Bridge” on his album O Dia Em Que Faremos Contato (The Day We Make Contact). Lenine’s songs span various musical islands and are difficult to categorize. He is at the vanguard of Brazilian rock and pop and is also an heir to the great eclectic tradition of post-bossa nova artists like Gilberto Gil, Djavan and Milton Nascimento, who established their careers in the 1960s and ‘70s. For Brazilian music fans that aren’t fond of the sertanejo, funk carioca and romantic samba that currently dominate the pop charts in that country, Lenine’s music is a welcome continuation of the work of the “MPB” generation of songwriters like Gil and Nascimento who like to blend strong melodies with rich harmonies, unexpected fusions and poetic lyrics.

Lenine’s polyglot songs seamlessly weave together rock, digital effects and the rhythms, instruments and poetic inflections of his hometown Recife. He shifts between being a lyrical, reflective troubadour and a rocker who vigorously plucks and strums an acoustic guitar, seeking a “dirty sound” full of overtones and syncopation. With the guitar, Lenine has invented a rousing funky beat that defies boundaries. Sometimes, Lenine veers into mangue beat territory with aggressive songs that mix electronic effects with strains of northeastern genres like maracatu and embolada. He may mix samples and filters with gentler folk styles. And he can evoke Peter Gabriel with soulful vocals, driving rhythms and big bass lines reminiscent of Tony Levin’s work. While Lenine carries Recife within him, he is a musical gypsy, at home in the Northeast, in Rio de Janeiro, and in foreign lands.

All the while, his lyrics are full of humanitarian sentiments and a romantic futurism informed by authors like Ray Bradbury. His words reference both contemporary reality in Brazil and images from science fiction. Lenine is a prolific songwriter whose work has been recorded by many leading Brazilian artists, a performer who frequently appears on others’ recordings, and an in-demand arranger and producer. His own albums, which he toils on for long periods, appear about every two to four years. He is a musician’s musician in Brazil and considers himself a craftsman. He is as popular in France as in Brazil and has appeared at WOMAD and many other festivals in Europe. And he has won five Latin Grammy awards.

The aforementioned O Dia Que Faremos Contato (1997) was a major step in Lenine’s evolution and earned him a Prémio Sharp award in Brazil for best New MPB Artist. He also won the award for Best MPB Song for “A Ponte” (The Bridge), written with Lula Queiroga, which sets his poetry against swirls of electronic noise, contains samples of repentistas Caju and Castanha, and features a stormy chorus (“Nagô, Nagô...”) backed by distorted power chords on electric guitar. By contrast, “O Marco Marciano” (The Martian Landmark) is a contemplative tune in which Lenine doubles his falsetto eerily over a ten-string viola (a type of steel-string guitar that is a mainstay of cantoria and música caipira). The lyrics evoke Ray Bradbury’s novel The Martian Chronicles, as Lenine sings of a “history of Mars buried by the ephemeral dust from storms” and a “Martian landmark with a person’s face, with the ruins of streets and cities” visible from the moons Phobos and Deimos. Throughout the album, Lenine mixes rock and pop with strains of coco, embolada, maracatu, aboio and various audio effects.

Na Pressão (Under Pressure) in 1999, produced by Tom Capone and Lenine, was another strong effort, selected by André Domingues in his book Os 100 Melhores CDs da MPB (The 100 Best MPB CDs). Naná Vasconcelos, a venerable figure in modern jazz who is also from Recife, supplies most of the percussion on the album. On the title track, his talking drum, bombo turco and caxixi back Lenine’s ten-string viola, which creates a northeastern mood that turns edgy and dramatic. The reflective “Paciência” (Patience) is one of Lenine’s most beautiful songs, and “Relampiando” (Lightning Striking) is a touching piece of social criticism. “Jack Soul Brasileiro” is a rhythmic tour de force, a primer in syncopation that fuses various elements. A few seconds of maracatu rural drumming open the song, and then Lenine strums his trademark funky groove on guitar and adds incredibly rhythmic singing that summons the tongue twisting wordplay of embolada. A version with a fuller arrangement is available on his Acústico MTV album.

Falange Canibal in 2001, continued Lenine’s fusion of the acoustic and the electronic, and won the Latin Grammy Award for Best Brazilian Contemporary Pop Album. Falange Canibal had more guest artists than any of his previous albums, including composer-keyboardist Eumir Deodato, members of the O Rappa and Skank bands, Frejat (of Barão Vermelho), singer-songwriter Ani DiFranco, trombonist Steve Turre, and drummer Will Calhoun and guitarist Vernon Reid from Living Colour. Lenine’s subsequent albums, such as Lenine InCité, Lenine Acústico MTV, and Labiata have won further awards. Yet such success did not lead Lenine to become a more commercial artist. Rather, in 2011, he released Chão (Ground), a beautiful, mellow, minimal album that has no percussion and incorporates ambient sounds from birdcalls to teakettles to typewriters to footsteps on gravel to heartbeats. Certainly, Lenine is taking Brazilian popular music across his metaphorical “bridge” to new horizons.

Band leader Martin Fondse, who leads the orchestra appearing with Lenine, is a Dutch pianist and composer who has won awards for his orchestral work and film scores. His work mixes jazz and many other musical styles, and he has collaborated with Peter Erskine, Terry Bozzio, George Duke, Vernon Reid and Pat Metheny, among others.

There is an extended profile of Lenine and interview with him in my book The Brazilian Music Book: Brazil’s Singers, Songwriters, and Musicians Tell the Story of Bossa Nova, MPB, and Brazilian Jazz and Pop.

An Olympian Night Life: Rio de Janeiro's Top Ten Clubs for Live Music

Rio de Janeiro has one of the most vibrant musical scenes on the planet, and includes both the incredible street celebration of Carnaval and a multitude of nightclubs for all tastes. Cariocas(natives of Rio) are generally gregarious, love music and aren’t shy about dancing, and the city’s nightlife is dynamic. Many of the hottest music spots are in the historic neighborhood of Lapa, a once neglected area that has been transformed into a musical mecca. Rio is associated with the birth of samba, choro and bossa nova, and its clubs offer lots of other styles as well.

In terms of music, there are many Brazils. Samba is the most famous musical genre and it comes in several varieties. Its infectious rhythms can make anyone get up and dance, yet one can also enjoy it in folksy pagode samba jam sessions with musicians and listeners seated around a table crowded with cold beer. For mellow evenings, there is sophisticated, subtle bossa nova (think Tom Jobim and João Gilberto), the instrumental pleasures of choro (usually played on acoustic guitar, flute and cavaquinho), and a wide spectrum of Brazilian jazz.

MPB mixed strong melodies, rich harmonies and eclectic influences beginning in the 1960s and ‘70s and is still going strong (Milton Nascimento, Gilberto Gil and Caetano Veloso are mainstays). A new generation of female singer-songwiters (Ana Carolina, Bebel Gilberto, Maria Rita and others) are creating much of the best MPB these days and mixing it freely with international pop.

The thundering rhythms of maracatudrums from Recife, the raucous Afro-Brazilian sounds of axé music (Ivete Sangalo, Claudia Leitte), and the playful, electronic beats of tecnobrega(Gaby Amarantos) liven up Brazilian dance floors.

You can go rural and romantic with the sertanejo genre, the local country music that is now the country’s most popular style. Or you might want to get down with funk carioca, raw and provocative dance music from the favelas, or Brazilian rap, Electro or Brazilian rock. Musically, there’s something for everyone. I give descriptions of Brazil’s different styles and leading artists in my books The Brazilian Sound (an introduction) and The Brazilian Music Book (a collection of interviews).

Here is a listing of ten memorable venues in Rio, mostly in Lapa, Centro (downtown) or the Zona Sul (South Zone). Call to confirm what style is playing and when the music starts, or ask the concierge at your hotel to call for you. The O Globo newspaper also has listings. Some clubs close on Sundays and Mondays. Most of these establishments have cover charges, usually the equivalent of U.S.$5 - $20, and expansive menus of great food.

Lapa and Centro have more than their share of crime. Take a taxi or Uber to your club and take one back to your hotel. Don’t wander far from your destination, unless you know your way around and are in a group.

Rua do Lavradio 20, Centro (close to Lapa); 3147-9000/9001/9002

http://www.rioscenarium.art.br (Portuguese/English)

2. The Vinicius Show Bar is an inviting spot devoted to the sublime, mellow sounds of bossa nova and named for poet/lyricist Vinícius de Moraes, who teamed with Tom Jobim on classics such as “A Garota de Ipanema” (The Girl from Ipanema”) and helped inspire and popularize the genre. One might also hear a little MPB or samba on some nights. Open Sun-Sat.

Rua Vinícius de Moraes 39, Ipanema; 2287-1497 / 2523-4757

Avenida Mem de Sá 79, Lapa; 2221-0043

http://barcariocadagema.com.br (Portuguese)

4. If you blink you might miss the tiny Bip Bip bar, which is located close to Copacabana Beach and is a fun place to catch pagode samba played casually around a table. Greats like vocalist Beth Carvalho sometimes stop by for samba on weekends. You can catch choro on Mondays and Tuesdays, and bossa nova on Wednesday night. Open most nights.

Rua Almirante Gonçalves 50, Copacabana; 2267-9696

5. Fundição Progresso is a larger space where well-known musicians play everything from MPB to rap to reggae to sertanejo.

Rua dos Arcos 24, Lapa; 3212-0800

http://www.fundicaoprogresso.com.br (Portuguese)

Praça Tiradentes 79, Centro; 2232-1149

7. Trapiche Gamboa is housed in a lovely old building and has great live samba for dancing (and occasionally choro). Open Tue-Sat.

Rua Sacadura Cabral 155, Praca Mauá; 2516-0868

http://www.trapichegamboa.com (Portuguese)

8.In Clube dos Democráticos, samba fills the dance floor most nights.

founded many decades ago as a Carnaval appreciation society. Wednesday nights explore the frisky northeastern forró style. Wed-Sat from 11pm.

Rua do Riachuelo 91, Lapa; 2252-4611

http://www.clubedosdemocraticos.com.br (Portuguese)

9. Lapa 40 Graus is a three-story club with all types of music: samba, choro, forró and sertanejo. Live music Wed-Sun.

Rua do Riachuelo 97; 3970-1338, 3970-1334

http://www.lapa40graus.com.br (Portuguese/English)

10. Astrophysicists who love to party or just those who like exotic nightspots should check out 00 (Zero Zero), an upscale spot housed inside Gavea’s planetarium. There’s a lounge, a dance floor and a mezzanine level where you can enjoy sushi. Live musicians and DJs play everything from samba to MPB to electro to reggae and jazz. Sunday is a gay afternoon/night. Open: Tue-Sun.

Planetário da Gavea, Avenida Padre Leonel Franca 240, Gavea; 2540-8041.

Also worth checking out:

Leviano (Lapa): electro, samba, jazz.

Saúde): no cover; samba.

Casarão Ameno Resedá (Catete): electic. And check out the DJs here:

Casa da Matriz (Botafogo): DJs: wide mix of music.

Fosfobox (Copacabana): DJs: wide mix of music.

O Rappa Co-Founder Marcelo Yuka Has Left Us

In 1993, reggae musician Papa Winnie was going to play in Brazil and need a local backing band. He picked four people -- Nelson Meirelles, Marcelo Lobato, Alexandre Menezes and Marcelo Yuka -- to perform with him. After Papa Winnie's shows were over, the four decided to stay together and they invited Marcelo Falcão to join them as their vocalist. The group debuted with the eponymous O Rappa (1994). They found success with Rappa Mundi (1996), produced by legendary rock producer Liminha, and Lado B Lado A (1999), produced by Chico Neves except for two tracks (including the title cut) produced by Bill Laswell.

Yuka became a paraplegic after being shot in a robbery in Rio in 2000. He left O Rappa the following year, because of artistic differences with lead vocalist Marcelo Falcão (Yuka went on to form the group F.U.R.T.O. in 2004). Yuka was O Rappa's most important songwriter while with them and penned many of the group's most memorable songs, including "Todo Camburão tem um Pouco de Navio Negreiro", "Me Deixa", and "Minha Alma (A Paz que Eu Não Quero)" e "Pescador de Ilusões." O Rappa stopped performing in 2018 and has no current plans to return.

Yuka's most recent release was Canções Para Depois Do Ódio in 2017 on Sony Music.

_______

Carnaval 2019

focusing on the escolas de samba (samba schools).

Images from AFP/Getty Images and Reuters.

So Long, João Gilberto

João Gilberto became one of Brazil and the globe's most influential musicians over the last sixty years, with his impact on Brazilian popular music, jazz and international music. For more on Gilberto and bossa nova, please visit the bossa-nova chapter in The Brazilian Sound. The book has been quoted in various João Gilberto obituaries, including these:

Also see: The Huffington Post: Blame It on the Bossa Nova (by Chris McGowan) and The Brazilian Music Book, my collection of interviews with Gilberto peers like Antonio Carlos Jobim and Carlos Lyra.

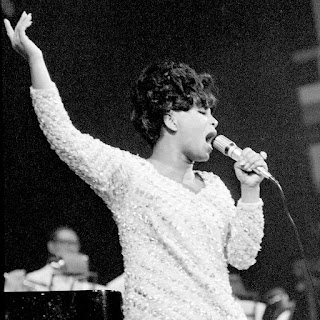

Elza Soares

Samba singer Elza Soares passed away on January 20 in Rio de Janeiro at the age of 91. She was born in 1930 in the favela of Moça Bonita (now Vila Vintem) in the neighborhood of Padre Miguel in Rio.

Elza Gomes da Conceição rose from poverty to stardom in Brazil and had a career that spanned seven decades and included 35 albums. She had a powerful, dramatic voice that she sometimes mixed with a raspy growl that earned her comparisons to Louis Armstrong. Soares explored many types of samba, as well as jazz, bossa nova, MPB, rock and electronic music. She was one of the first Brazilian singers to mix samba with scat vocals in her debut album, Se Acaso Voce Chegasse (If You Happen to Show Up). released in 1960. Soares won many honors in her lifetime, including a Latin Grammy award for Best MPB Album for Mulher do Fim do Mundo(Woman at the End of the World, 2015).She had four Latin Grammy nominations for other works. In 2016, she sang in the opening ceremonies of the 2016 Olympic Games in Rio de Janeiro.

The Brazilian Music Book

Brazilian Music Book (Australia) Brazilian Music Book (Germany)

Brazilian Music Book (Italy) Brazilian Music Book (France)

Brazilian Music Book (Spain) Brazilian Music Book (Japan)

Brazilian Music Book (India) Brazilian Music Book (Mexico)

Free Kindle reading apps (U.S.)

_______

Festival Vale do Café 2014

|

| Performing at one of the fazendas. |

A unique Brazilian music event, the Festival Vale do Café (The Coffee Valley Festival), began on July 7 and runs until July 27 in the small towns and old coffee plantations of verdant, historic areas in and around the city of Vassouras, about two hours from Rio de Janeiro. The focus is primarily on jazz, choro, bossa nova, regional styles and classical music. Concerts are free in the public squares and churches of Vassouras and nearby cities, while tickets are required for the intimate music shows staged at stately fazendas (plantations).

Singers Fafá de Belém and Joanna will perform this year in free concerts, while the Bianca Gismonti Trio, Duo Santoro, Nicolas Krassik e os Cordestinos, Gabriel Grossi, Orquestra Carioca do Choro, Turibio Santos, Carol MacDavit, Gilson Peranzzetta, Mauro Senise, Cristina Braga, Bia Bedran and Trio Madeira Brasil will also make appearances. During the festival, many free music classes are offered for children. One night (the Cortejo de Tradições) is devoted to folia de reis, capoeira, jongo, cana-verde and other folkloric traditions, peformed by local groups. This is the 12th year of the festival, which was created by harpist Cristina Braga. Guitarist Turibio Santos and Paulo Barroso are the event's artistic directors.

|

| The main house of an old fazenda. |

|

| Turibio Santos (guitar) and Cristina Braga (harp). |

|

| The main square of Vassouras during the festival. |

|

| João Bosco at the festival in 2013. |

Read about Brazilian Music

and the Popular Music of Brazil

by Chris McGowan and Ricardo Pessanha (Temple University Press)

MIMO Festival Boasts Spectacular Scenery and Performances in Four Cities

|

| Paraty, Brazil |

|

| Trilok Gurtu |

|

| Bongar |

|

| Toninho Horta |

|

| Renata Rosa |

Sérgio Mendes Talks About "Brasileiro"

In 1992, I was invited by Elektra Records to write the liner notes for the Sérgio Mendes album Brasileiro, which was unlike anything he had ever done.The trademark Sérgio Mendes sound (upbeat, with female voices singing in unison) was there but it was mixed together with the idiosyncratic Carlinhos Brown from Bahia, who contributed five songs and was the cornerstone of the album, three great Brazilian songwriters (Ivan Lins, Guinga, and João Bosco), and the instrumental wizard Hermeto Pascoal and his band O Grupo. Plus the 15-member Bahian percussion group Vai Quem Vem and a hundred drummers and percussionists from the top Rio escolas de samba (samba schools) were there to keep things cooking.

A Simple Way to Save a Life / Salvar uma Vida

We can save millions who have blood diseases now. Nearly everyone has a family member who has had one or knows of someone who has had leukemia or another blood illness. Please help just by registering.

The Updated Brazilian Sound Kindle Edition

“Well researched . . . . its breadth of coverage is impressive.” —Randal Johnson, Hispanic American Historical Review

“Enlightening descriptions of musical styles.” —Martha Carvalho, Popular Music

Free Kindle Reading Apps (from Amazon)

Free Kindle reading apps (U.S.)